Talking about the Chicago Teachers’ Strike

First published in January/February 2013 edition of The Bullhorn. The original publication can be found here.

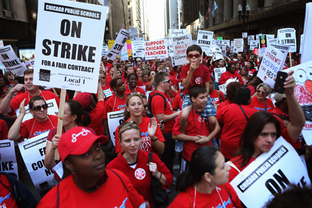

At the beginning of last semester, Chicago streets were covered in red to represent the union behind the counter-movement against the corporatization of the Chicago public education system. The Chicago Teachers Union amassed support not only from teachers, but from parents and children yearning for improved conditions for the city’s youth, especially in marginalized communities. After eight days, they won the strike, ushering in the beginning of a potential movement across the nation for union and educational advances. Tacoma, Washington teachers began striking on September 12th, the day after Chicago teachers first crowded the streets. On January 15th, Chicago witnessed its sixth battle for rights this past academic year in the Grayslake Teachers’ Strike. Nationwide, people want to know what the strike means for the future of public education, and that interests fuels progress.

On November 8th, SUNY New Paltz hosted a talk entitled “Chicago Teachers’ Strike: Reframing Education Reform and Teacher Unions,” focusing on educating attendees, including students, faculty, and community members, on the environment behind the strike, the initiatives behind its success, and implications locally and nationally. The talk started with a lecture by speaker Pauline Lipman, followed by a question-and-answer session.

Pauline Lipman combines educational examination with active political engagement in her passionate interest for Chicago’s public education system. As a Professor of Educational Policy Studies and Director of the Collaborative for Equity and Justice in Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago, she devotes her research to race and class inequality, globalization, and the political economy of urban education. Her latest book, The New Political Economy of Urban Education: Neoliberalism, Race, and the Right to the City (Routledge, 2011), observes critical geography, urban sociology, anthropology, critical race analysis, and educational policies in Chicago to offer solutions for problems in urban schools and city life as a whole. She is also involved with Teachers for Social Justice, the Chicago Teachers Union, and active in struggles against school closings across Chicago and the rise of charter schools since 2004. After years of fighting for teacher’s rights and jobs in the “corporate education epicenter,” her experiences in the Chicago Teachers’ Strike became personal.

Lipman structured the talk as not just an academic observation of the events, but as a personal account of the strike. On the first day, she saw all the protesting teachers standing on the street curb, eventually forming into huge throngs that took over downtown Chicago. Rush hour cars constantly honked in solidarity, and one could not hear themselves over the horns and rallying teachers. Out of twenty-six thousand teachers, only twenty crossed the picket line. She accompanied her talk with many pictures, some of which are reprinted in this article, that clearly demonstrate the strength of the effort and support from the community. “People, wherever you were, were recognizing the teachers and were in solidarity with the teachers.” Lipman particularly highlighted the strong tie between educators and families, since “too often, in a lot of urban school districts, there is a disconnect between parents and teachers.” Parents and their children provided food and water to those striking, and students even joined with their own picket signs.

Why now, when there is a strong history of parent-teacher disconnect in urban schools? First, there was a common enemy, forming a multiracial coalition in solidarity with the striking teachers; Rahm Emanuel already infuriated African-American and Latino communities by closing down public schools and privatizing them, but he also found opposition in white, middle-class parents by stripping funding for music and art programs and extending the school day with no additional resources. Second, the teachers were not just fighting for wages and benefits for themselves, but for what students need in their schools. Third, Lipman concludes that “finally someone had stood up to the powers that be, so that all the things that people face in the city—privatization, the inability to find decent housing, police brutality, you name it—here was a group of people in an organized, grassroots, militant way that actually stood up to it… They became heroes.”

A revitalized Chicago Teachers Union, mobilized and organized for a strong strike, secured success. Three years before the momentous event, the union was “essentially demobilized,” weakened by school closings and unable to fight for worker benefits. From that rock bottom point, in 2008, CORE (Caucus of Rank-and-File Teachers) formed within the union, focused specifically on an anti-neoliberal and anti-corporate agenda. Once elected to CTU leadership in 2010, the union prioritized organizing and research, which were unprecedented efforts in the CTU. Developments allowed creative, diverse rallies throughout the city, each with a certain subject in mind, raising larger issues of education, race, and classism that educated the public through picketing and signage, since the union could not strike over anything besides money and hires. Such topics included TIFs (siphoned-off tax dollars from schools and parks into “development” funds), charter schools, and a lack of psychological counselors in high crime-rate areas. CTU also reestablished strong chapters within all Chicago public schools, mobilizing teachers to demand their rights. Through all these efforts, the organization created the basis for a social movement union, and “raised up an example of what an union could be like, compared to what that union was three years ago, when most teachers didn’t want to be in the union, to the point where we were at where twenty-six thousand teachers went out on strike.” Members, who were never activists before, became politically conscious and aware of how to organize and fight for rights.

Towards the end, Lipman reminded us that this is only the first step. “These are all battles, built upon each other,” to preserve the public sector and fight against the national shift towards privatization in more than just education. Yet, as a model for future movement, the Chicago Teachers’ Strike will not be ignored in the overall struggle for middle-class liberties and activism.

The recorded event is available online at: http://newpaltz.mediasite.suny.edu/Mediasite/Play/e32712a7f83741deb8cf3467f72616021d.

The latter half includes the question-and-answer session that touched upon topics such as standardized testing, specific effects of the strike on minority communities, high school and college student activism, problems with charter schools, CTU outreach, and how to understand the strike in relation to a plethora of national issues.

On November 8th, SUNY New Paltz hosted a talk entitled “Chicago Teachers’ Strike: Reframing Education Reform and Teacher Unions,” focusing on educating attendees, including students, faculty, and community members, on the environment behind the strike, the initiatives behind its success, and implications locally and nationally. The talk started with a lecture by speaker Pauline Lipman, followed by a question-and-answer session.

Pauline Lipman combines educational examination with active political engagement in her passionate interest for Chicago’s public education system. As a Professor of Educational Policy Studies and Director of the Collaborative for Equity and Justice in Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago, she devotes her research to race and class inequality, globalization, and the political economy of urban education. Her latest book, The New Political Economy of Urban Education: Neoliberalism, Race, and the Right to the City (Routledge, 2011), observes critical geography, urban sociology, anthropology, critical race analysis, and educational policies in Chicago to offer solutions for problems in urban schools and city life as a whole. She is also involved with Teachers for Social Justice, the Chicago Teachers Union, and active in struggles against school closings across Chicago and the rise of charter schools since 2004. After years of fighting for teacher’s rights and jobs in the “corporate education epicenter,” her experiences in the Chicago Teachers’ Strike became personal.

Lipman structured the talk as not just an academic observation of the events, but as a personal account of the strike. On the first day, she saw all the protesting teachers standing on the street curb, eventually forming into huge throngs that took over downtown Chicago. Rush hour cars constantly honked in solidarity, and one could not hear themselves over the horns and rallying teachers. Out of twenty-six thousand teachers, only twenty crossed the picket line. She accompanied her talk with many pictures, some of which are reprinted in this article, that clearly demonstrate the strength of the effort and support from the community. “People, wherever you were, were recognizing the teachers and were in solidarity with the teachers.” Lipman particularly highlighted the strong tie between educators and families, since “too often, in a lot of urban school districts, there is a disconnect between parents and teachers.” Parents and their children provided food and water to those striking, and students even joined with their own picket signs.

Why now, when there is a strong history of parent-teacher disconnect in urban schools? First, there was a common enemy, forming a multiracial coalition in solidarity with the striking teachers; Rahm Emanuel already infuriated African-American and Latino communities by closing down public schools and privatizing them, but he also found opposition in white, middle-class parents by stripping funding for music and art programs and extending the school day with no additional resources. Second, the teachers were not just fighting for wages and benefits for themselves, but for what students need in their schools. Third, Lipman concludes that “finally someone had stood up to the powers that be, so that all the things that people face in the city—privatization, the inability to find decent housing, police brutality, you name it—here was a group of people in an organized, grassroots, militant way that actually stood up to it… They became heroes.”

A revitalized Chicago Teachers Union, mobilized and organized for a strong strike, secured success. Three years before the momentous event, the union was “essentially demobilized,” weakened by school closings and unable to fight for worker benefits. From that rock bottom point, in 2008, CORE (Caucus of Rank-and-File Teachers) formed within the union, focused specifically on an anti-neoliberal and anti-corporate agenda. Once elected to CTU leadership in 2010, the union prioritized organizing and research, which were unprecedented efforts in the CTU. Developments allowed creative, diverse rallies throughout the city, each with a certain subject in mind, raising larger issues of education, race, and classism that educated the public through picketing and signage, since the union could not strike over anything besides money and hires. Such topics included TIFs (siphoned-off tax dollars from schools and parks into “development” funds), charter schools, and a lack of psychological counselors in high crime-rate areas. CTU also reestablished strong chapters within all Chicago public schools, mobilizing teachers to demand their rights. Through all these efforts, the organization created the basis for a social movement union, and “raised up an example of what an union could be like, compared to what that union was three years ago, when most teachers didn’t want to be in the union, to the point where we were at where twenty-six thousand teachers went out on strike.” Members, who were never activists before, became politically conscious and aware of how to organize and fight for rights.

Towards the end, Lipman reminded us that this is only the first step. “These are all battles, built upon each other,” to preserve the public sector and fight against the national shift towards privatization in more than just education. Yet, as a model for future movement, the Chicago Teachers’ Strike will not be ignored in the overall struggle for middle-class liberties and activism.

The recorded event is available online at: http://newpaltz.mediasite.suny.edu/Mediasite/Play/e32712a7f83741deb8cf3467f72616021d.

The latter half includes the question-and-answer session that touched upon topics such as standardized testing, specific effects of the strike on minority communities, high school and college student activism, problems with charter schools, CTU outreach, and how to understand the strike in relation to a plethora of national issues.